In 2022, House Bill 9 added rules for funding Kentucky charter schools. Those new provisions call for each charter school to share in most of federal, state, and local revenue available in their “district of location.” With that intent quite clear, the implementation is still going to be challenging. My big suggestion for working on the challenges is that we start building prototypes: models of what sample charter schools might receive based on the students they serve and the districts where they are located. Here, I’m going just dive in and show my understanding of key calculations, starting with SEEK base funding.

SEEK Base Basics

SEEK is short for Support Education Excellence in Kentucky, our main formula for funding public education. With only small modifications, we’ve used this approach since 1990, with a base guarantee for every pupil and a set of add-on amounts for students with additional needs. Here’s an illustration for an imaginary district. It starts with total students, counted based on average daily attendance, and then shows each group of students that receives an add-on. For simplicity, it uses the $4,000 guarantee amount being used this fiscal year.

Local school boards use their taxing powers to raise 30¢ for every $100 of taxable property in their districts, and that taxation raises varying amounts depending on districts’ assessed property values. The state then pays whatever is needed to complete the guarantee, which means state contributions are higher in districts with less property wealth and lower in districts with more.

SEEK Base For Charter Schools

Under HB 9, a public charter school is to receive:

“The amount that is proportional to the public charter school's enrollment or average daily attendance in comparison with the overall district qualifying numbers for:Funds that are related to students' attendance and enrollment and allocated to the district of location pursuant to KRS 157.360.”

KRS 157.360 is the statute that sets up the base part of the SEEK formula, so here’s my prototype of that step for two imaginary charter schools. These schools have matching numbers of total students but quite different student needs. Like the district numbers above, it begins with total students in average daily attendance and follows with the add-on amounts that go with the current $4,000 base guarantee.

This part of the funding will be the same everywhere in the state, though in future years the amounts per pupil will likely be at least little higher. Each charter school will receive these dollars from its “district of location,” but the amounts won’t vary based on the school’s address.

Tier 1 Optional Equalization

In addition to the guaranteed base, the SEEK formula allows districts to get some further state equalization called Tier 1, up to a maximum of 15% of the district’s SEEK base total. All districts are taking that maximum. The part the district puts in depends once again on its taxable property, but this time I want to illustrate how that works at three different levels of property wealth:

Because of the equalization, the property wealth doesn’t matter to what districts receive. Will it matter when districts pass dollars to charters? Maybe.

Tier 1 for Charter Schools

When Tier 1 dollars are shared out:

- Will charter schools get shares based on qualified enrollment with all the weighting, giving Charter A 6% or the revenue and Charter B 3.8%? That would add about $283 thousand for Charter A and $179 thousand for Charter B.

- Or will each get 5% and $236 thousand, based just on the count of pupils and ignoring the add on needs?

- Or (take a deep breath), will they get the state dollars based on qualified enrollment and the local dollars per pupil? If it’s done that way, the district’s property assessments will matter. The richer the district, the more revenue will be local. The more the revenue is local and handed out without weights, the less the Charter A’s higher need students will receive.

As an advocate for equity that meets student needs, I definitely prefer the qualifying enrollment approach.Here’s the thing: after a week of reading HB 9’s funding provisions over and over again, I see how others could argue for either of the other methods. xI also think the stakes are big enough that key players are likely to argue hard for the version that works best for the students they expect to serve. Here's a table showing how differently the three approaches could work.

Other Puzzles

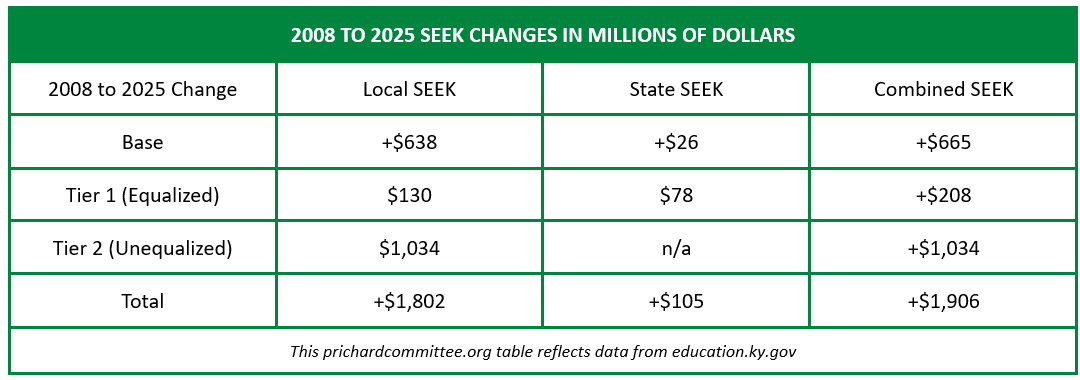

For each other part of school funding, my hunch is that there will be other puzzles to work through. Those other parts include:

- SEEK transportation

- SEEK Tier 2 (unequalized local dollars capped at 30% of base plus Tier 1)

- SEEK-funded stipends for National Board Certified Teachers

- SEEK funds for a variety of facilities costs

- State funding for school technology

- State funding for other categorical programs

- Federal funding for categorical programs

Each of these streams is worth prototyping the charter allocations and discussing with care. This is about big money and there will be big concerns. The best time to start working on those big issues is now, with maximum time to think through implications, consider any proposals to clarify the legal language, and (if possible) dependable information for all concerned.

Impact on Other Schools

None of this is going to be easy for any district where families choose a charter option. For example:

- Districts have multi-year commitments to staff, equipment, utilities and building upkeep, and none of those commitments will shrink by 5% if enrollment changes by that proportion.

- For any “district of location” where a charter school opens, in addition to amounts to be paid, there will be timing issues. Local revenue often comes from property taxes paid between November and January, so it will matter how much has to be paid out to each charter school before that November cash flow arrives.

- For those districts of location, there will also be the disruption of having their local tax revenue divided up to pay for students whose homes (and family tax contributions) are in other school districts.

- For other districts, when students leave to go to charter schools in other areas, there will also be disruptions. Eligibility for each kind of state and federal funding may decline. If local revenue is stable, that will offer the most cushioning to districts where the highest taxable property produces the largest local contribution.

At least for moment, try thinking of this as similar to the financial implications of a divorce with children involved. To give just one example, even if the division of property and income is done perfectly, the money that paid for one home will not pay for two homes at the same level of comfort. Dividing education revenue among more schools is going to require stretching the same dollars to cover more spaces and equipment and sorting out those changes will involve new negotiations, drafts and revisions, compromises and conflicts.Some readers are sure to think charters will have benefits worth the effort. Others are sure to think they won’t. Over time, some on either side may move toward the other view. For now, I want to offer a simpler point: funding charter schools is going to take effort. There are puzzles to be solved, and those solutions are likely to generate more puzzles. That work is right in front of us, and it needs attention.Adding a caveat: The prototype possibilities shared above are the best I can figure out on my own. It’s completely possible that readers who follow school funding will immediately see flaws in my reasoning. That’s kind of the point of sharing a prototype: it lets us find the glitches early. So please, bring on the questions, concerns, and alternate views of how this will work.

Legal sources: In 2022's House Bill 9, Section 7 has the rules for funding charter schools. (See pages 30 to 35). KRS 157.360 shows most of the rules for SEEK base funding, with the add-on for students with limited English proficiency shown only in budget legislation like 2022’s House Bill 1. House Bill 1 also provides that the SEEK base guarantee will move up from $4,000 to $4,100 next year and $4,200 the year after: the calculations above kept the $4,000 figure because it makes the arithmetic easier to follow. KRS 157.440 shows the Tier 1 and Tier 2 rules.

Series Links:

Charter schools: taking on the questions (Introduction)

2. What student results are charter schools expected to deliver?

3. Which school laws do charter schools have to follow?

4. How can students be admitted to charter schools?

5. Who can authorize charter schools?

6. Who can apply to start a charter school?

7. How can charter schools be closed if they do not deliver?